How do we write and where do ideas come from?

That’s too big a question for me to solve, but it was the topic of a recent Six Pixels of Separation podcast, in which host Mitch Joel interviewed Mark Levy. Levy went on at length about free writing, reminding me that some of the best ideas come from writing down…anything, and finding the good ideas come out best when they are forced out with all the crap. I won;t say I necessarily practice free writing exactly as Levy espouses it, but I embrace the higher concept.

Brainstorming

As I listened, in my mind I applied this to the idea of brainstorming, reminding myself that the best brainstorms in which I have participated consisted of a “no wrong ideas” policy– later we would cull the ideas for the ones we would actually use. Thinking of “anything” helped shake loose the “big things.”

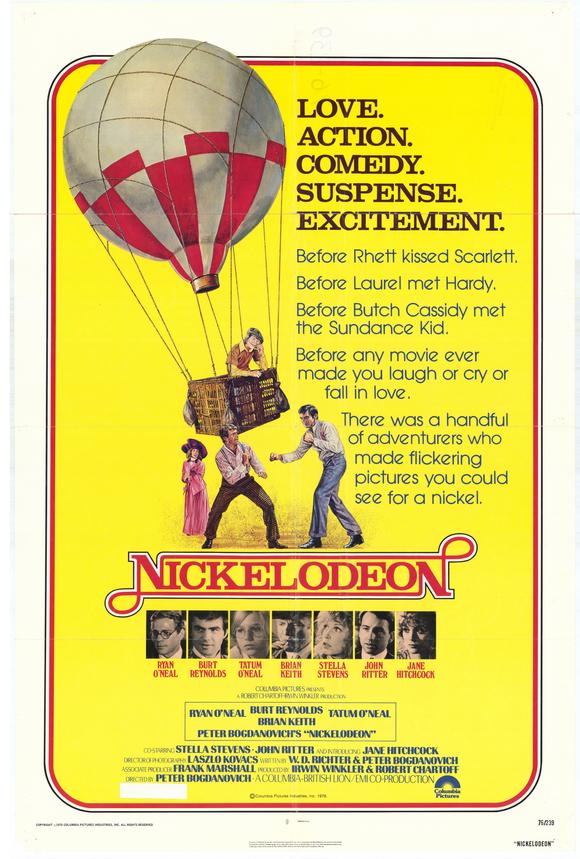

In the early days of movies, I have heard- and seen depicted in the Peter Bogdanovich film “Nickelodeon” – that filmmakers would bring a sort of ringer – an “idea man” – to story sessions. This ringer, quite possibly a crazy person (in some fashion), was hired specifically for his propensity to spit out the most ridiculous ideas that anyone- well, actually nobody else- would think of. the result? None of those ideas would show up in the films, but it loosened up the other writers to the extent that they could come up with ideas on their own that might otherwise be hard to reach.

In the early days of movies, I have heard- and seen depicted in the Peter Bogdanovich film “Nickelodeon” – that filmmakers would bring a sort of ringer – an “idea man” – to story sessions. This ringer, quite possibly a crazy person (in some fashion), was hired specifically for his propensity to spit out the most ridiculous ideas that anyone- well, actually nobody else- would think of. the result? None of those ideas would show up in the films, but it loosened up the other writers to the extent that they could come up with ideas on their own that might otherwise be hard to reach.

So, with lone “free writing”, or team brainstorms, I would recommend bringing in- or manufacturing (or becoming) that “crazy” who makes it alright for others to unearth their wilder ideas.

Also, one thing I say often: who are you to say your ideas are stupid? You’re truly not qualified. Let your audience decide.

What Are You Afraid of?

The primal directive of this whole rant brings me back to the “just do it” notion of writing, or creating any media. Free flow of any ideas to break brain lock, but also letting go of the fear that your ideas suck.

They don’t.

I have written here before that “Chris Brogan is not smarter than you.” Of course, that depends on context, but what I really meant is that you shouldn’t be afraid to do something just because someone else is pretty successful at doing something well. Everything has a bunch of practitioners. David Ortiz doesn’t stop trying to hit home runs for the Red Sox just because his career will not measure up to that of, say, Ted Williams, or, to name a contemporary, Albert Pujols. That doesn’t mean he cannot be a good hitter, and it certainly doesn’t mean there is no place for his talents, just because we already have a Pujols to watch.

Free writing and “crazy” brainstorming are means to open up the idea flow, but the notion that you simply need to do it is also important.

This brings me to a slight digression, but not really: Amber Naslund’s post in her “Brass Tack Thinking” blog, “Four Reasons the Social Media Industry Has a Credibility Problem.” Clearly, she is fed up with the propensity for many of us in the social media industry to tear each other down. The premise of that argument is that people rip each other over jealousy of success. I think a lot of that is a reaction to the opposite; building up some people over others, not necessarily on the basis of talent or merit, but on perception and opportunities taken by the “rock stars.” So, have at it and criticize when you think something is wrong. I for one, believe it is healthy, and that when you get held up to a standard you simply need to develop a thick skin.

Oh wait, where was I going with this? The “rock star worship” pretense that has arisen out of some social media circles, I fear, may make some people think their ideas are unworthy. They aren’t. Just share them, and don’t worry about how they stack up, because they probably stack up better than you think.

Even though I conducted this interview… I keep going back to re-listen to it… I learned so much… I’m glad you did too :)

Doug, I love the sentiment of this post. With the gurus attempting to generate ideas and concepts that can be branded and applied to any and all business situations, people lose sight of the fact that no two businesses are the same and the approaches can vary, have feedback, be adjusted and succeed. Having the courage to strike out into un-familiar and un-charted territory intellectually is sometimes hard to come by, for sure, but even if you’re screwing up and succeeding a little, at least you won’t blend in with the masses. That’s valuable too, no?

Well, the other thing (to stretch the Ortiz example to the breaking point), one need not be perfect in order to be successful. After all, how many times does the man strike out, or not hit it quite hard enough to be a home run? Yet he still has a job, with rather sweet pay, and the adulation of his fans.

When and where, exactly, did we all get the idea that the only acceptable condition was perfection?

Janet,

I won’t advocate a .300 batting average in this case, but good point