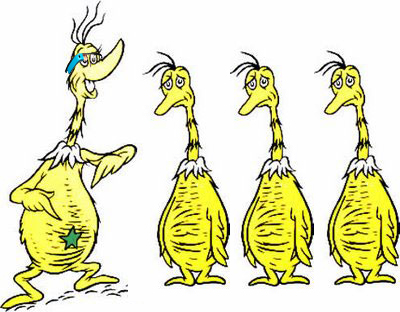

Of Blue Checkmarks and Sneetche

The butthurt by Twitter power-users who don’t get their Verified Account checkmarks is still being heard ’round the world. I, too, was nonplussed after giving it a shot; seeing some of the non-celebrities who seem to have gotten theirs, and Twitter opening up the request process, I thought why not? I was more entertained by the fact that my rejection email didn’t make it through my spam filter. Alas, I will not be going to the Verified frankfurter parties. That about sums up the whole value of my effort, and the Verified Account process for most of us. Perhaps the program does determine who are the best Tweeters and who are the worst, but if they truly opened the program, how in the world will we know if which kind is what or the other way round?

Would it kill Twitter to reward longtime loyal users who still frequent the platform with a Verified status? What about longtime holders of potentially valuable simple handles (like @DougH and @Genuine), who have been targeted by hackers and identity theft? On the other hand, if the purpose of Verified Accounts was to protect the identities of actual well-known figures and brands (as opposed to self-important social media consultants), then why open the process at all? I guess it all got some of us talking about Twitter, which, short of getting acquired or improving their trending topics to take advantage of Facebook’s recent failures in that regard, or taking care of spam issues (see below), will have to do.

Those checkmarks aren’t so big. They are really so small. You might think such a thing wouldn’t matter at all. Twitter Verified Account program manager Sylvester McMonkey McBean was unavailable for comment.

No Comments No Problems

Comment sections on news sites have long been a problem. They tend to be a morass of anonymous trolling and hideous opinions that are the glutenous mass that evolves into worse forms of harassment on the social web. How to solve the issue? Community, open discussion and engagement by brands are supposed to be the golden promise of the social web, but when Letters to the Editor take on the form of a digital equivalent of bricks thrown through windows, is it worth it?

Some publishers got used to it, and even embraced their seemingly damaged community- I was fascinated by this of some of their regular pseudonymous commenters several years ago- and you may be also.

Many bloggers have wrestled with the “real names” requirement. Of those I read, Northeastern University journalism professor and media expert Dan Kennedy has gone back and forth, as many of his politically-charged topics have created problematic comments. Recently, he went back from a longstanding “real names” policy because there are many people who have legitimate reasons for wanting to be anonymous – or at least can be counted on to behave, whatever their handle.

Another recent trend has been to rely on Facebook for the conversation: come to our site for the content, please leave for the discussion. I noticed this on Esquire, which has a politics page that invites readers, at the end of each article, to join the discussion on their Facebook page. As a reader, I found that to work well in practice, where in theory I might have had doubts. The publisher can still moderate discussion as they see fit, and the riffraff can play their reindeer games (or not) without sullying the sacred Esquire.com real esate. It makes sense and works well, to the extent that Facebook remains a Thing.

NPR made news more recently, removing their comments sections as of August 23. One stated factor is the fact that many people prefer to comment (and share) on social media anyway, but I suspect the potential cost of cleaning up the hate mess that comment sections often turn into is more of a factor – that channeling conversations to Facebook is less costly (though, again, still needing moderation).

Does this trend mean community is dead? No, it means it must be managed, and there are many ways to do so with the resources you have (or want to devote). I’m sure I’ll check back n on this when the next trend emerges because something bad happened on Facebook.

Someone Should Start a Hashtag on Why You Shouldn’t Use Infographics

This is actually intriguing, but I wonder how complete it is: a study shows hashtag effectiveness is hard to measure because spammers can overwhelm them. I am skeptical. I easily can believe that spam Twitter accounts target hashtags. However, does that mean they are useless? Can you still, say, count 35% of hashtag use (to take a number from the study) as an effective measure of how many non-spam accounts are sharing your hashtag organically? I suspect you can use “because spammers are ruining it” as a reason to discount any function of Twitter. Are hashtags the problem? No, the wasteland of fake and spammy accounts on Twitter are- and perhaps, if it’s possible, that’s a better job for Twitter’s Fix-It-Up Chappies than creating a Checkmark-On Machine.

I embedded the infographic at the very end of this post because it’s too darn huge to put in the middle, and I’m not done just yet.

Pinch Me, am I Dreaming? Instagram Has Added an Incremental Feature!

Sometimes it takes the little things to make people go nuts. Now you can zoom on Instagram images. Hooray?

I can’t wait to try it. I guess.

Here’s that dang huge infographic

Hashtag Spam | Infographics

I must say it was hard to find your page in search results.

You write awesome posts but you should rank your blog higher in search engines.

If you don’t know 2017 seo techniues search on youtube: how to rank a website Marcel’s

way